With the Paris Agreement, the EU’s burden-sharing agreement and the Danish agreement on a Climate Act, climate politics has moved from the global level to the European level to the national level. Now, it is time for the next step of the climate policy. Delivering on the political goals will move out to the workplaces and into the Danes homes.

Workers will play a key role. They will implement the specific climate initiatives and find further potentials. And they must – in line with employers, students and retirees – make adjustments in their homes and everyday lives.

The challenge of climate change

The global greenhouse gas emissions are steadily increasing. In 1970, approximately 27bn tonnes of CO2e were emitted[1].

In 2017, these emissions had doubled. And even though the corona crisis will lead to a temporary decline this year, the development is expected to continue towards 2030.

The increased concentration of greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere causes climate change. The UN’s climate panel predicts an average temperature rise of up to 5 degrees Celsius by 2100 if the development continues at the current rate.

In Denmark, we have already had a taste of one of the possible direct consequences: Extreme weather where drought is followed by flooding, which entails economic costs.

In many countries, the consequences are far more serious than in Denmark. And consequences abroad can also affect Denmark indirectly in the form of refugee flows and lower growth.

For these reasons – and because of our historical responsibility and current carbon footprint – Denmark has a strong interest in solving the global challenge of climate change.

Climate change and the economic costs it causes can be limited if the global greenhouse gas emissions are reduced markedly. And this makes sense since the costs of inaction by far exceeds the costs of reducing emissions.

“The costs of inaction are far greater than the costs of reducing emissions.

Our climate targets for 2030 and 2050

In 2015, 194 countries adopted the Paris Agreement which contains a long-term goal to hold global average temperature increase well below 2 degrees Celsius and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

In 2017, the EU’s burden-sharing agreement followed, and in December 2019, a large majority in the Danish Parliament agreed that Denmark should adopt an ambitious and binding Climate Act with the goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 70% in 2030 and a long-term goal for climate neutrality by 2050, at the latest.

The work towards 2030 and 2050

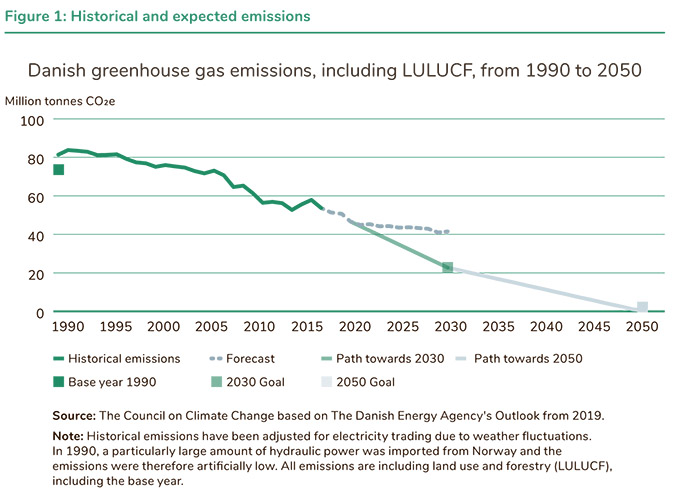

Fortunately, some progress has already been made towards the 2030 and 2050 goals. From 1990 and until 2017, Denmark’s greenhouse gas emissions decreased from 75.2m to 51m tonnes CO2e, and due to policies that have already been adopted, they are expected to decrease further to 41.5m tonnes[2] by 2030.

We can therefore expect an approximate reduction of 46% in 2030, even in the absence of additional initiatives.

A reduction of 24 percentage points thus remains. This corresponds to approximately 19m tonnes CO2e, including emissions and removals from lands and forests (LULUCF).

The final reductions, however, will be the hardest. Many low-hanging fruits have already been harvested. For example, we have already reduced a large part of the coal consumption and stopped straw burning. The goal cannot be achieved with one single initiative.

The remaining reductions, however, will be the hardest to achieve. Many low-hanging fruits have already been harvested. For example, we have already reduced a large part of the coal consumption and stopped straw burning. The goal cannot be achieved with one single initiative.

A large part of the investments can pay for themselves over time in the form of energy savings and exports.

In this way, towards 2030, the challenge will grow because we already need to lay the tracks to achieve the long-term goal of climate neutrality in 2050.

The buildings that we construct today and the forest we plant will still be there in 2050 and they will either be part of the solution or part of the problem.

The challenge is complicated by the risk of carbon leakage. If companies exposed to competition are regulated too heavily, there is a risk that production is moved abroad, to the detriment of global climate initiatives as well as the Danish economy and employment.

Meeting the 2030-target will therefore not be easy.

Funding requirements and sources

In its report, “Known paths and new tracks for a 70% reduction”, the Danish Council on Climate Change has assessed that the “socio-economic cost for Danish society” for achieving the 70% target will, by 2030, reach 15-20bn a year.

However, this assessment is based on a narrow focus on cost effectiveness, and it is important to keep in mind that behavioural changes over time can erode revenues from taxes and duties on fossil fuels, among other commodities.

Finally, the total financing needs, which in this report are calculated as additional investments and immediate costs[3], that an initiative entails towards 2030, compared to a less climate friendly alternative[4], will be greater than the socio-economic costs.

The Council on Climate Change also points to this. The Climate Partnership for Energy and Utilities alone estimates a need for additional and extra investments amounting to approximately DKK 350m towards 2030.

Importantly however, a large part of the investment will be repaid over time – not just in the form positive effects on climate change but also in the form of energy saving and exports.

This applies to building renovations and wind power, among others. The financial sector has also declared that it intends to invest DKK 350bn in green loans and investments towards 2030.

At the same time, Denmark’s Green Future Fund, which was established in 2019 with a capacity of DKK 25bn, and EU funds, would be able to fund a number of initiatives.

Just as there is a need for many different measures in many different sectors, there is a need for different sources of funding. This means that there is a need to look at both public and private opportunities.

Building on this, figure 2 clearly shows that workers find that the task of ensuring the green transition must be solved collectively and not by the private companies or individuals alone. As many as 61% believe that the task should mainly be solved on a collective basis. The underlying survey and other findings of the report are described in box 1.

Box 1: FH’s work-life survey, 2020

The majority of the figures in this report reflect the outcome of a survey on the views of workers on their working lives and the green transition carried out by Statistics Denmark for FH.

The survey includes replies from a representative sample of 2,790 workers and unemployment benefit claimants between the ages of 18-74. The interviews have been carried out in February and March 2020.

The questions in this report have been answered by 2,579 respondents.

1,489 of the respondents worked in the private sector and 996 worked in the public sector. 252 of the respondents had no further education beyond primary -and lower secondary school, 181 had completed upper secondary school, 864 had completed vocational training 794 had completed short- or medium-cycle higher education and 488 had completed long-cycle higher education.

The three roles of workers

To achieve the ambitious goals, we will have to exploit solutions we already know. However, as pointed out by the Council on Climate Change, we will also have to develop new solutions. In both instances, workers play a key role.

Firstly, it will be workers who implement many of the known solutions through their daily work. Wind turbines must be built, charging stations must be installed and buildings must be renovated.

Secondly, workers must be involved in identifying new emissions reduction potentials. Processes must be rethinked, business models must be developed, new solutions must be invented and exported to the benefit of the environment, growth and employment.

The implementation and development of solutions will require qualifications. New investments into training and education and skills development will be needed.

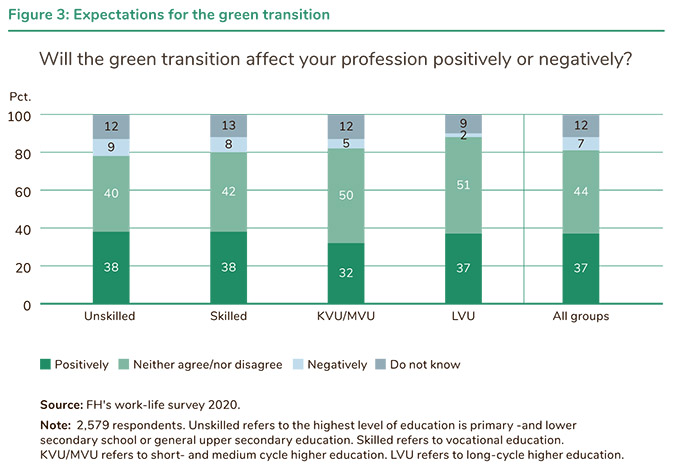

Workers trust that the transition will benefit their working lives: Figure 3 shows that 37% expect a positive effect on their occupation while only 7% expect a negative effect.

Optimism is therefore more than five times greater than pessimism. To the optimists, the positive expectations are based on trust in better health and safety at work, new green jobs and more meaningful lives, as shown in figure 4. The optimism is only, to a lesser extent, based on expectations for better pay. Only 20% expect better pay.

When it comes to the 7% who expect a negative effect on their occupation, their concern revolves around competitiveness, losing their jobs and job functions and new skills demands.

This points to the need to ensure that workers are able to change careers and that a social safety net is in place – for example in the form of an unemployment benefit system that provides security when the job situation becomes precarious.

Thirdly, workers, as well as employers, must join in the efforts to meet the objectives in their homes and everyday lives. For example, this can be by replacing the oil heating boiler with a heat pump, by sorting waste and by observing dietary guidelines.

Rising to the challenge in daily life and at home may require better funding opportiunities. And it may require addressing social and economic inequalities. The relative cost of an oil heating boiler, for example, is higher for low-paid workers than for high earners.

Social justice and collective solutions

The new everyday tasks and the concern that the transition can lead to job losses, loss of job functions or demand for certain skills give rise to questions regarding social justice..

Figure 5 shows that workers – across income groups – find that it is important that the green transition is socially just. This is in line with the outcome in figure 2 which shows that there are many who believe that the task is to be solved collectively.

The respondents worry about competitiveness, losing their jobs, job functions and new skills demands.

This belief in the importance of social justice is particularly widespread among low- and middle-income earners but also among high-income earners.

Workers across income groups find that it is important that the green transition is socially just.

Literature reference

[1] CO2-equivalents is a term describing different greenhouse gasses, including methane and nitrous oxide, in a common unit.

[2] The Danish Ministry of Climate, Energy and Utilities (2019),“Climate policy report: The report on the climate policy by the Danish Ministry of Climate, Energy and Utilities to the Danish Parliament.

[3] A number of immediate costs are included, among other things a number of operating costs, such as climate-friendly public sector food procurement, climate-friendly slurry- and manure handling and strengthened export efforts.

[4] If an oil heating boiler is to be replaced and the price of a gas furnace is DKK 30,000 while the price of a climate-friendly heat pump is DKK 80,000, the investment of the measure constitutes DKK 50,000.