The 10 areas:

- Bigger roles and initiatives for the public sector

- Strategic commitments to Power-to-X, circular economy and bioeconomy, carbon capture and storage, and research

- Sector coupling underpinned by major energy investments

- More climate-friendly installations, structures and buildings

- A more circular economy, better disposal and management of waste

- Climate-friendly food-development, consumption, agriculture and forestry

- Transportation: Reform of car taxation and heavy transport

- Green transition of business and industry

- International initiatives regarding climate, competitiveness and exports

- Climate taxes and other sources of financing

Together, these initiatives would deliver the 19m tonnes CO2e-reductions allowing us to achieve our 70% goal by 2030.

FH’s master plan contains a total of 113 proposals. The first part of the plan proposes 89 specific climate initiatives covering 10 areas – from green and socially sustainable purchasing in the public sector to more offshore wind farms and carbon taxes[6].

Together, these initiatives would deliver the 19m tonnes CO2e-reductions, allowing us to achieve our 70% goal by 2030. We assess that the total green transition will create at least 200,000 more full-time equivalents in Denmark.

Denmark in 2030

If the plan is implemented, Denmark will have met its ambitious climate target and will be an international pioneer country – not just based on greenhouse gas emissions but also in the area of Power-to-X-technologies, circular economy and bioeconomics.

The new solutions, such as hydrogen, alternative proteins and climate-friendly materials will contribute to reducing emissions in other countries and exporting them will benefit growth and employment in Denmark. Thanks to a mixture of subsidies and carbon taxes adjusted to the individual sector, our industry and agriculture will be developed, not dismantled.

Denmark will, at the same time, have demonstrated how the transition goes hand in hand with equality and social justice. Citizens will receive better education, and thereby, better opportunities for contributing actively to the transitions – among other things through a strengthening of worker participation.

There will still be people who will continue to drive petrol- and diesel driven cars, but there will be 700,000 electric cars on the Danish roads in addition to hybrid cars.

More people will have green jobs, and for people who are affected because their jobs disappear, there will be greater security and better possibilities for skills development than today. People will continue to choose what they eat themselves, but they will be better informed, and the carbon footprint from food production will have been considerably reduced.

The state will have driven the technological endeavours by defining “missions” by setting a course for initiatives and cooperation and by providing venture capital. The majority of the investments will be funded by private operators who have seen green potential and a good scope for returns.

The price paid by the Danes will, among other things, be in the form of carbon taxes – for example on air travel – changes in car taxation, mandatory replacement of oil heating boilers and gas furnaces, and inconveniences in connection with waste sorting, expansion of wind turbines, biogas plants and infrastructure.

For most people, however, this price will be outweighed by energy savings, more nature, smarter cities, better opportunities for jobs and training, increased labour market security and ownership of the green transition.

There will therefore continue to be wide support for the transition and for the next target of climate neutrality by 2050.

Impact on climate change: The plan accomplishes the 2030 target

Ea Energy Analyses (Ea) has assessed FH’s combination of climate initiatives and the impact on climate change of key proposals (other proposals are considered to facilitate the transition but do not have an independent effect on emissions).

The purpose of the assessment was to ensure that the initiatives do not overlap or mutually exclude one another and that their estimated effect on emisions is valid.

There are many linkages and value chains across sectors and it is therefore often meaningless to ascribe obtained reductions to one sector alone.

For some initiatives that involve changes in consumption, part of which the estimated impact on climate change could be outside Denmark, Ea has estimated the national effect to constitute 50%.

Some of the initiatives that require a significant amount of research, such as new feed additives in agriculture, are subject to considerable uncertainty.

Based on its assessment of the initiatives, and with the above reservations, it is Ea’s assessment that the expected impact on climate change, when all initiatives are implemented, constitutes a reduction of approximately 19m tonnes of CO2e, in addition to the reductions that are part of Denmark’s Energy and Climate Outlook (DECO19) from the Danish Energy Agency. In this way, a 70% reduction compared to 1990 will be achieved.

Table 1 shows the reduction’s distributed to the sectors that are described in the following chapters while figure 6 shows the distribution between specific initiatives. It is important to keep in mind that many of the initiatives are cross-sectoral and are dependent on the other initiatives.

Sectors, sectoral applications and collective solutions

As shown in table 1 and figure 6, the main part of the reductions are, for the most part, driven by the reductions in the energy sector which is expected to have reduced its emissions by almost 100% in 2030.

However, a simplified focus on different sectors and the relative contribution of certain initiatives is not useful. There are many linkages and value chains across sectors and it is therefore often meaningless to ascribe obtained reductions to just one single sector.

For example, the agricultural sector contributes to the production of biogas which replaces fossil fuels in transportation and industry, while requirements for green and socially sustainable public procurement in the public sector drive the implementation and development of solutions in the areas of installations, structures and buildings, transportation and trade. Often, a solution in one sector necessitates an initiative in another sector.

Table 1 and figure 6 therefore do not reflect the cross-cutting value chains and preconditions and therefore not the actual contributions of the sectors. For example, reductions due to an increase in the use of heat pumps, which are attributed to the energy sector in the table, can also be attributed to trade, industry and agriculture.

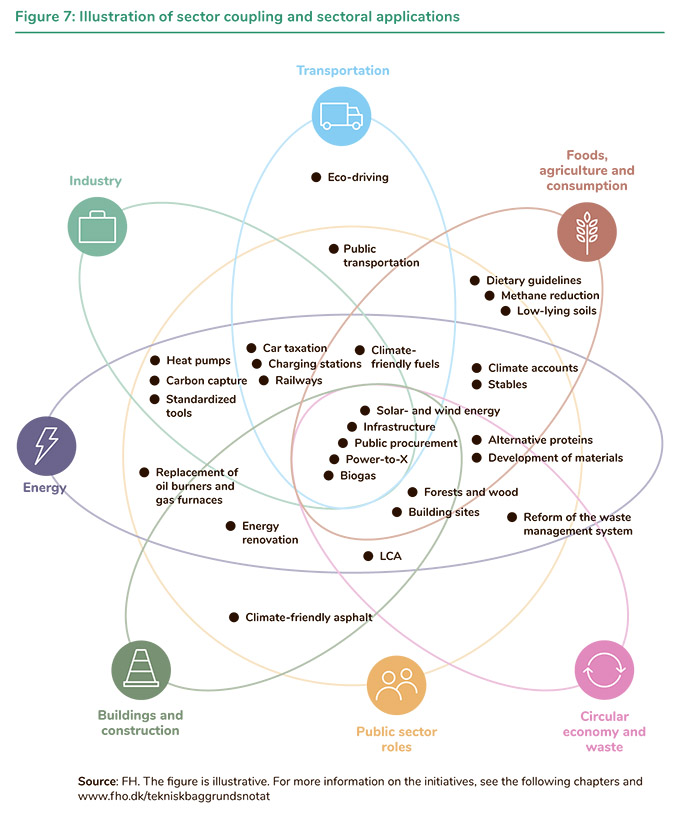

Figure 7 provides a more accurate representation of the individual initiatives and contributions of the sectors. It shows how a number of initiatives intersect with six different sectors as well as the public sector. It can be seen from the centre of the figure that some initiatives play a key role in the transition as they affect all areas.

This could be the development of solar- and wind energy, Power-to-X and public procurement. The contributions from these initiatives cannot be ascribed to just one sector. The solutions are collective.

It can also be seen that the public sector – which is another expression of collective solutions – plays a role in almost all of the selected initiatives. That role can be to set the direction, be a coordinator or to be a regulator/investor. At the same time, the state also owns critical infrastructure.

These strategic roles for the state, regions and municipalities were, to some extent, overlooked in connection with the government’s climate partnerships which did not include a partnership with the public sector.

Meanwhile, the roles of the state as a driver for development and transition are recognised to an increasing extent[7]. And in connection with the corona crisis, the state’s ability and capacity to shape society has become clearer – perhaps in Denmark more than in any other country.

Uncertainties and continuous follow-up

The expected reductions and the achievement of the 2030 goal are subject to uncertainties. Firstly, the exact impact on climate change from research and development is uncertain, see above.

Secondly, Denmark’s emissions – and thereby the need for reductions – depend on societal developments that are unlikely to be exactly as the climate outlook predicts today. Finally, new cost-efficient and socially just solutions can emerge.

For those reasons, there should be continuous follow-up of the initiatives and the achievement of objectives until 2030. The plan should not be seen as a definitive solution for the entire duration of the period.

If it turns out that further initiatives are needed, for example if research into feed additives does not meet the expectations of the climate partnership with the Danish agriculture and food sector, it will make sense to take more organic soils out of production than initially suggested here.

Employment: At least 200,000 full-time equivalents

The green transition in Denmark will have significant positive effects on employment. For the initiatives that the Economic Council of the Labour Movement has calculated on behalf of FH alone, at least 200,000 additional full-time equivalents will be created from 2020 to 2030.

This exceeds the employment effect of four Fehmarn Belt Fixed Link construction projects according to earlier estimates from Copenhagen Economics[8]. An ambitious 10 GW energy island with the related investments would create a further 150,000 full-time equivalents.

Many of the full-time equivalents will be created in rural areas. This applies to full-time equivalents associated with the expansion of biogas, wind energy and infrastructure.

Today, central Jutland and the southern part of Denmark already hold most of the so-called “green” jobs in Denmark, see figure 8.

At the same time, the initiatives also create new full-time equivalents in larger cities, for example in connection with energy renovation. This creates a geographical balance in terms of the effects of the plan.

The impact on employment is a conservative estimate. It only includes the temporary jobs created when establishing the initiatives – for example, the establishment of an offshore wind farm – not the permanent jobs that for some proposals will be rooted in permanent operations and maintenance.

Furthermore, it must be noted that the impact on employment does not reflect the total quantity of “green full-time equivalents” created. The employment effect does not reflect that the initiatives can lead to a decline in other full-time equivalents as a consequence of the shift in investments from traditional to green investments.

This is illustrated in figure 9 where the change to the total number of full-time equivalents shown by the impact on employment is smaller than the change in the number of green full-time equivalents.

At the same time, it is important to note that not all of the calculated full-time equivalents will be green in the sense that they reduce emissions when considered in isolation.

For example, some of them are created in trade or transportation, which are not traditionally considered ‘green’. All the full-time equivalents created, however, contribute to underpinning the green transition.

Figure 9 illustrates that the transition can lead to the loss of some job functions.

This is one of the reasons why the plan suggests that proposed legislation and capital investments on climate change should be subject to impact analysis regarding the impact on employment with a view to ensuring active implementation of solutions where they are needed, and municipal and regional climate strategies must specifically address “just transition”, including solutions for businesses and citizens.

All in all, it can be expected that the 200,000 full-time equivalents estimate is on the low side and that the transition will create even more full-time equivalents towards and beyond 2030. It is important to underline, however, that the estimates are subject to considerable uncertainty.

At least 200,000 full-time equivalents will be created from 2020 to 2030. This corresponds to an impact on employment which is more than four times that of the Fehmarn Belt Fixed Link construction project.

Health and safety at work, training and education, skills development and security on the labour market

It is not enough for the green transition to create more jobs. It must create more good jobs. At the same time, we must ensure that those who are to fill the new jobs have the right skills and that there will be new opportunities and support for the ones whose job functions disappear.

Health and safety at work, training and education, skills development and security are necessary preconditions for the transition.

The final part of the report will outline a total of 24 proposals in these areas.

Financing needs

When it comes to the initiatives for which it has been possible to assess the financing needs, it has been estimated that the total financing need towards 2030 will be approximately DKK 230-450bn.

The range listed in table 1 of DKK 390-437.7bn includes the financing of a number of initiatives that have already been agreed in the energy agreement of 2018 and reflects an increase in electricity production which is more than what is required for domestic consumption and which therefore allows exportation of green energy[9]. The financing need does not include costs for continuation of initiatives beyond 2030 etc.

The estimate is – as in any assessment looking 10 years ahead – subject to considerable uncertainty. The cost of the transition will, ultimately, depend on both the politically chosen initiatives, developments in technology, behaviour and initiatives in other countries.

DKK 230-450bn may seem drastic. Many of the investments will, however, provide a return and the main part is therefore expected to be financed by private investors. This applies to, for example, extension of wind energy, infrastructure and investments into the development of Power-to-X and biorefining.

The public sector is expected to provide financing at a maximum amount of DKK 75bn, depending on the co-funding of private investors, grants from the Danish Green Investment Fund and EU funds. Specific FH proposals for financing are listed below.

In addition to providing a financial return, many of the investments will bring socio-economic benefits. For example, energy renovation could contribute to a better indoor climate in schools, and afforestation can contribute to biodiversity and a better aquatic environment.

Such positive effects are not included in the investment need but contribute to making the initiatives good investments.

FH’s plan distinguishes itself from other proposals

The FH master plan distinguishes itself from other proposals and recommendations presented by other parties. Five characteristics can be highlighted:

The five characteristics:

- The proposals as a whole address all major sectors, not just agriculture, energy or transportation, and defines a strategic and active role for the state.

- FH’s proposals do not only address technology but also a number of broader and necessary conditions for meeting the 2030 and 2050 targets: Training and education, health and safety at work, equality and security on the labour market. 24 proposals in these areas are presented in the final part of this report.

- FH’s proposals give priority to development instead of dismantling. For example, investments into Power-to-X, carbon capture, alternative proteins, climate accounts and feed additives must be made rather than actively reducing animal production or banning the sale of petrol cars which lead to carbon leakage, reduced mobility and social imbalance. Out of the total reductions of approximately 19m tonnes of CO2e, the above solutions provide 5.4m tonnes, which corresponds to more than 25%.

- FH’s proposals have a greater international focus than that of the Danish Council on Climate Change, for example, as it focuses narrowly on Denmark’s national targets. Solutions like Power-to-X, alternative proteins and climate-friendly materials could potentially be exported or extended to other countries and have a global effect. In addition to this, the FH proposal limits carbon leakage by providing subsidies for industry and agriculture and by combining carbon taxes in Denmark with a carbon border tax in the EU.

- FH’s proposals on carbon taxes, foods and car taxation are balanced, reasonable and practical. The solutions are beneficial for the climate but do not create social imbalances, carbon leakages or disproportionate costs for the state. As for carbon taxes, which have been discussed for a long time, FH proposes a specific path forward and deadlines for implementation.

Literature reference

[6] Go to https://fho.dk/tekniskbaggrundsnotat for more information on the proposals.

[7] See, for example, Mazzucato, Mariana (2013), ”The Entrepreneurial State: debunking public vs. private sector myths”, Anthem Press: London, UK.

[8] Copenhagen Economics (2013), ”Documentation of the economic-wide employment impact of a the Femern Belt tunnel construction”, for Femern A/S June 2013).

[9] The financing requirements for the energy and utilities sector listed in table 1 at the amount of DKK 329-432.7bn are based on the specifications of the needs for additional investments of the climate partnership in question (Kpenergi, 2020). In this case, it is important to keep two aspects in mind (EA, 2020). Firstly, the need for additional investments contains a number of pre-arranged initiatives that are part of the climate outlook for 2019, including the establishment of three offshore wind farms, the expansion of biogas and infrastructure. These initiatives are included here because they involve a genuine investment need and a real impact on employment towards 2030. Secondly, the climate partnership initiatives deviate from the FH initiatives in a number of areas. Among other things, the climate partnership requires more electricity, among other things due to more low-emission vehicles. On the other hand, FH’s initiatives include a number of additional measures such as, for example, more carbon capture. Ea assesses that, based on input from the climate partnerships and FH, the total required additional financing needed constitutes approximately DKK 230bn, not including financing for the agreed measures under the energy agreement, and the immediate costs which are included in the DKK 329-437.7bn in table 1 above.