This would strengthen the incentive to use climate-friendly technologies or consume climate-friendly goods. Most recently, the Council on Climate Change and Kraka/Deloitte have proposed a uniform tax on greenhouse gas emissions in Denmark, and figure 15 shows that there is widespread support for a uniform carbon tax.

Challenges and barriers to climate taxes

While a uniform carbon tax works well in theory, there are a number of significant challenges. Three in particular are important:

- Distributive effects: Higher carbon taxes specifically affect goods and services in energy consumption, food consumption etc., and this will affect low income groups the hardest. The immediate effect of carbon taxes is therefore higher inequality.

The inequality can be counteracted by more extensive tax reforms, but these can result in a lower supply of labour and leave people who are particularly exposed to the challenge of carbon leakage without a solid foothold on the labour market. - Carbon leakage: A production tax on CO2-emissions risks pushing Danish production abroad, where companies are not subject to similar requirements. This will reduce the global impact of Danish initiatives and lead to loss of Danish workplaces.

The leakage problems can be met with a sector-specific basic allowance, but it is unclear whether, and to what extent, the basic allowance would work as intended. - Practical implementation: The carbon footprint of a specific product is often difficult to calculate. This is, especially, the case where production chains are cross-border and in agriculture, where emissions and capture are part of complicated biological processes.

In addition to this, there is limited knowledge on the price sensitivity of different products/services, including how significant changes to taxes would be required in order to obtain an actual behavioural effect, and thereby a climate effect.

Reason and balance

FH recognises that there may be good theoretical arguments in favour of a carbon tax. At the current time, however, it is unrealistic to implement a uniform carbon tax without sufficient regard for inequality, carbon leakage and practical implementation.

Instead, there is a need for a more long term, sensible and balanced strategy which ensures the necessary regard for distribution and which reduces the risk of carbon leakage.

First and foremost, the idea of a perfect, uniform carbon tax must not get in the way of sector-specific solutions that work for the climate, industry and humans, and which do not exclude a harmonization of taxes in future. In some sectors, carbon taxes can be introduced in the short term.

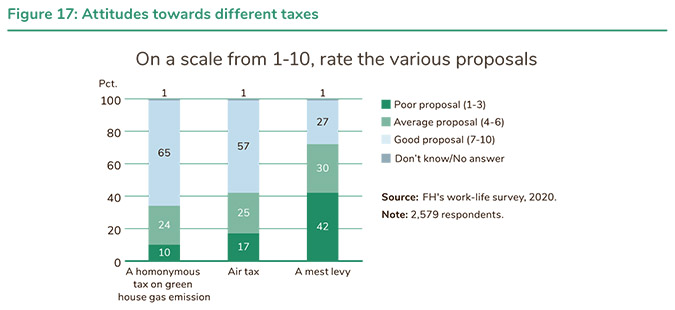

This could, for instance, be in aviation, where figure 16 shows that there is wide support among Danish workers. As many as 57% find it to be a good proposal, while only 17% find it to be a poor one. In comparison, only 27% believe that a tax on meat is a good proposal, as can be seen in figure 17.

In other sectors, however, there is a need for more knowledge and longer phasing in or of other solutions. At the same time, considerations about taxes must take into account the effects of the corona crisis.

FH’s proposal for a carbon tax

On this basis, FH proposes an overall initiative based on three elements. First of all, an expert commission must be set up and tasked with designing carbon taxes for each sector taking into account the following binding principles:

- The tax must reduce emissions and/or create an incentive for technology development. It must be examined whether the tax will lead to a genuine behavioural effect and whether it can be implemented without large administrative costs.

- The tax and phasing-in must not lead to considerable carbon leakage. This can be ensured, among other things, by promoting/conditioning international cooperation and regulation in other countries and/or by a deduction for companies exposed to competition.

- The proceeds and the distributive effects must be documented and it must be specified how the proceeds should be used to counteract a possible increase in inequality.

Secondly, a binding political goal should be defined according to which, based on the work of the expert commission, a plan for the implementation of carbon taxes should be ready before the end of 2022. And by 2025, carbon taxes should be introduced to the extent that they meet the above principles.

Thirdly, an aviation tax should be introduced at a level which would affet either consumer behaviour or the incentive for airlines to reduce emissions. The tax should be progressive, for example through a higher tax for business class or long-distance trips.

In connection with the three elements, it should be clarified how the proceeds from carbon taxes are best applied, i.e. taking distribution, carbon leakage challenges and climate impact into account. In this regard, it may be relevant to reduce the standard electricity tax and electric heating charge.

Box 12: FH proposes

- An expert commission should design carbon taxes taking into account the impact on climate change, development of technology, risk of carbon leakage and inequality.

- Mobilisation of private financing

- Loan financing/green bonds

- Financing by the Danish Green Investment Fund and through green bonds from KommuneKredit (credit association with the purpose to provide loans to Danish municipalities)

- Financing through income tax

- Establishment of a unit that facilitates repatriation of EU funds.

Read more at: https://fho.dk/tekniskbaggrundsnotat

Other sources of financing

Carbon taxes can both strengthen the incentive for climate initiatives and bring proceeds that contribute to financing the green transition. The proceeds, however, will not be sufficient to cover a financing need of DKK 230-450bn.

First of all, since carbon taxes are expected to be introduced gradually they cannot contribute considerably in the short term.

Secondly, proceeds from carbon taxes can be expected to decline over time as the taxes lead to an (intended) change in behaviour, for example fewer flights. There is therefore a need for more sources of investment.

Mobilisation of private financing

Private financing must be mobilised in order to cover the main part of the DKK 230-450bn financing need. The potential is large, since most investments can provide a return, and the investments will therefore be interesting to private investors such as banks, pension funds and insurance companies.

This applies to, for example, investments into the expansion of offshore wind energy, energy efficiency measures in buildings and biorefining. In 2019, pension- and insurance companies have declared that they will offer DKK 350bn in green loans and investments in Denmark and abroad.

A minor share of the financing need must be covered by individual companies and households. Among other things, this applies to the installation of heat pumps. However, FH proposes that government subsidies are applied to a wide extent.

You are now reading Chapter 10. Climate taxes and other sources of financing.

Read also:

01. Greater roles and measures for the public sector

02. Strategic commitments to Power-to-X, the circular economy, bioeconomics, carbon capture and research

03. Sector coupling underpinned by major energy investments

04. More climate-friendly installations, structures and buildings

05. More circular economy, better disposal and management of waste

06. Climate-friendly development of foods, consumption, agriculture and development of forests

07. Transportation: Reorganization of taxation of cars and transformation of heavy transport

08. A green transition of business and industry

09. International initiatives regarding climate, competitiveness and exports

Government bonds and the Green Investment Fund

The state is expected to provide a maximum of DKK 75bn of the total financing need.

These funds will primarily finance subsidies and investments. Part of the funds can – due to the negative interest rate and low level of government debt – be obtained by issuing bonds to provide financing for selected initiatives through, for example, the Danish Green Investment Fund. The fund already has a capacity of DKK 25bn and, in 2019, Holland raised almost DKK 45bn by offering green bonds at an interest rate of 0.5%.

A number of the initiatives that require the most financing can, in the long term, generate a return. In this way, the state can recoup its investments. This is the case for, among others, Power-to-X, development and upscaling of biorefining and development of new materials.

Finally, the credit rating of the Danish state and the low level of debt must be used as a stepping stone to provide the Green Investment Fund, KommuneKredit and other state funding schemes with a bigger mandate and scope of action in their daily work – to the benefit of the green transition in private and public companies and institutions.

Repatriation of EU funds

At the EU level, there are a number of possibilities for financing climate efforts in Denmark, including in the field of research (Horizon), agriculture (The EU’s Common Agricultural Policy) and environment and climate (LIFE). Today, Danish ministries and other players already work hard to repatriate funds, but the work will be even more important in the future in light of the large investment need required to meet the 2030 target.

The government must therefore establish a unit to facilitate the repatriation of EU funds by ensuring an overview of the financing possibilities, an overall strategy and even better opportunities for entrepreneurs, companies, researchers and authorities.

This initiative should also be in the interest of the EU system as better projects from the individual member states ensure that the EU funds have a greater effect.

Financing through income tax

Even after the above initiatives have been brought into play, a financing gap may remain. This can be the case for specific investments towards 2030 and permanent additional costs in connection with the continuation of initiatives after 2030, including the operation of platforms, export initiatives and climate accounts, as well as revenue loss.

The financing gap can make it necessary to consider financing through income tax. There are a number of advantages related to income tax, including a progressive distribution of the burden and a steady income that allows for financing of recurring costs and revenue loss. At the same time, however, income tax also has downsides.

It is a burden on the taxpayers and reduces the supply of labour. Figure 18 shows a certain willingness for income tax financing among Danish workers: 58% are willing to contribute with 0-1% through income tax in order to ensure financing of the green transition.

FH is open to the idea of financing a part of a coming climate action plan by means of income tax if the financing challenge cannot be solved through sources, including, for example, carbon taxes, mobilisation of private financing, loan financing and financing from Denmark’s Green Future Fund and KommuneKredit.

This principle is intended to ensure that other instruments are given priority and are exhausted before income tax financing is used.

In 2019, Holland raised almost DKK 45bn by offering green bonds.

You just finished reading Chapter 10. Climate taxes and other sources of financing.

Read all chapters below: